Bank of Japan is boxed in!

BoJ can't escape unless it breaks what it set out to prevent in the first place.

Some context first.

In the 1990s, Japan had an asset bubble problem. Real estate and stock prices were rising like anything. And when that bubble burst, Japan faced two full decades of stagnation - the lost decades, as they call it at Harvard. Read if you want to know more.

To counter that, Japan reduced its interest rates to zero. It put a cap on government bond yields so that the borrowing cost remains low. Such an ultra-loose policy would normally invite inflation. But for reasons that require a separate post, inflation did not pick up for the next 20 years.

Surprisingly, over the last 2 years, the situation has been changing. Finally, inflation is coming back to Japan. It’s more like the climax scene for Bhuvan from Lagaan when the rain finally hits his face.

It was a dream come true for the Bank of Japan (BoJ), the central bank of Japan.

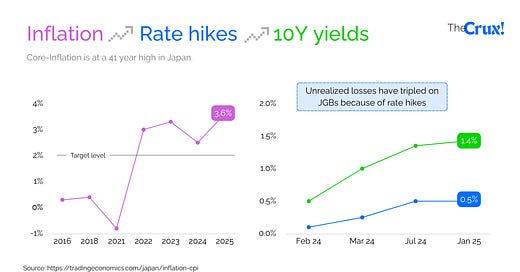

When inflation was consistently above its 2% target for ~2 years, BoJ began gradually exiting its ultra-loose monetary policy and conducted its first rate hike in 17 years in March 2024. And the second one in July 2024. And the third in Jan 2025.

That’s a lot of action in quick succession for a central bank that has stayed put for 2 decades.

As rates went up, bond prices fell, and the yields on those bonds went up.

Interest rates and bond yields have a proportional relationship.And this is precisely the point where the problem begins.

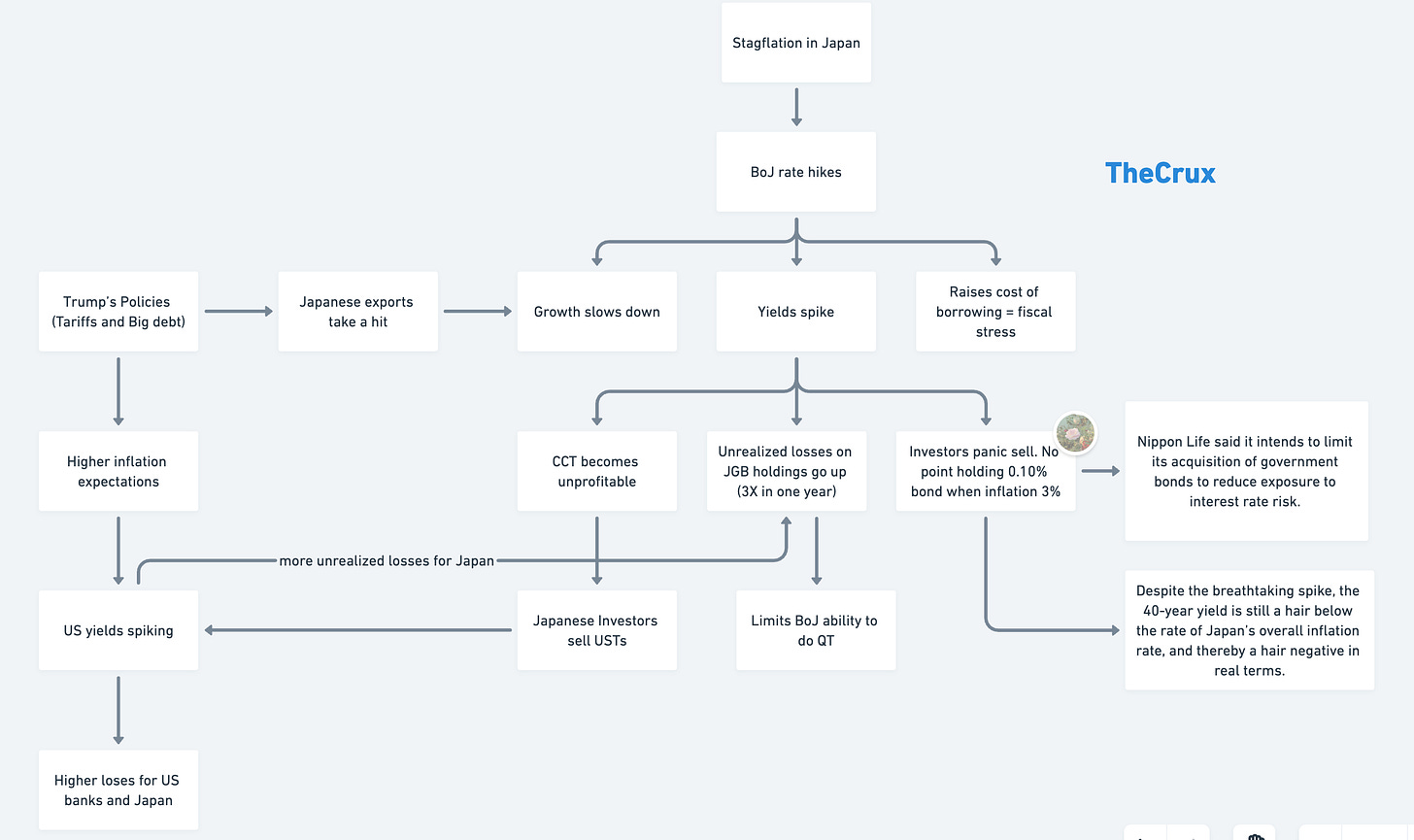

The inflation Japan is experiencing is not the inflation Japan wanted.

Good inflation is when the price goes up because demand goes up. And demand goes up because wage growth and consumer demand go up. That’s BoJ’s wet dream. A solid demand-pull inflation.

But in reality, Japan is facing a cost-push inflation, which erodes purchasing power without lifting real incomes. This is bad inflation.

Japan's GDP shrank by 0.4% in Q1 2025.

Growth has been sluggish: ~0.9% in 2024, with flat or negative predictions for 2025.

Real wages remain stagnant or negative, undercutting consumption.

Rice prices have doubled in one year. People are feeling the pain on the ground. And this violates any central bank’s primary objective: price stability.

So, BoJ did what any central bank should: raise interest rates and sell bonds.

3 successive rate hikes and a bit of quantitative tightening. This is quite aggressive given Japan’s historical stance.

But are they enough? Despite steep hikes, both interest rates and bond yields lag behind the inflation rate, which suggests they could go even higher.

Is Japan prepared for such high yields? What could be the implications?

The implications of higher bond yields.

1. Increasing unrealized losses

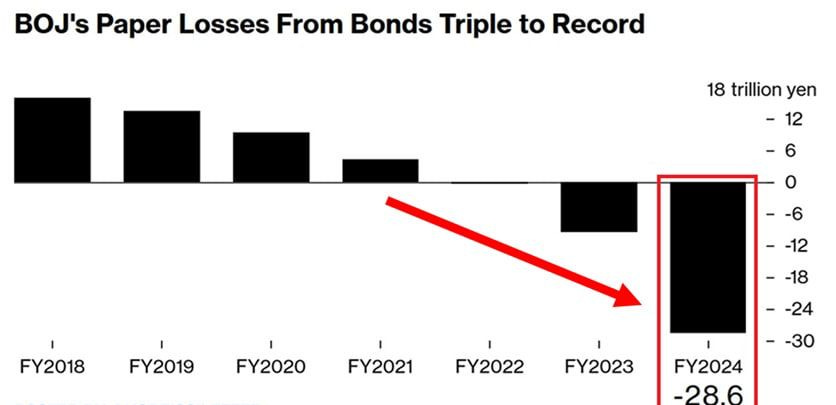

Yields have gone up so sharply that BoJ’s own unrealized losses from government bond holdings have tripled in one year.

Higher unrealized losses restrict a central bank’s ability to do quantitative tightening. You issue a bond for 100. 100 goes into the money supply. If you distress sell, you receive less. A lesser amount gets reduced from the money supply. Media houses are now questioning the central bank’s ability to instill confidence in the system when it is itself on the brink of a portfolio collapse. However, this article refutes such arguments, and I agree.

But forget the central bank for a moment. What about ordinary investors?

Why would someone hold a 0.10% bond when inflation itself is 3-4%? That’s a negative return in real terms. And this is particularly concerning for people who bought super-long bonds. For 30-40 years.

Longer the maturity, higher the price sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations.And who buys long-dated bonds? Insurance companies or pension funds, to match their asset-liability. So, who will get screwed the most? Insurance companies and pension funds.

Nippon Life Insurance, Japan’s biggest life insurer, said unrealized bond losses on its books have tripled in one year. Read more here. These institutions have two options now. Either hold till maturity and collect that meager 0.1% and make negative returns, or cut loose and book losses. Nippon has already realized ¥500 billion in losses through bond sales during the fiscal year. The spokesperson has said more selling is underway.

Same with all other insurers.

2. Currency Carry Trade is getting less profitable

A quick explainer on CCT.

Currency carry trade depends on the difference between US and Japan rates. Higher the difference, higher the profit on this trade. But as Japan hikes rates, CCT becomes less profitable than it was before.

At 3-4% yield on JGBs, a Japanese investor is better off borrowing in yen and investing the proceeds in JGBs itself rather than taking foreign currency risk in investing in US Treasuries. This means lower demand for USTs, which in turn puts more pressure on US bond yields.

3. GDP’s growth is getting slower.

In Japan, every sector is facing one headwind or the other.

Exports are 20% of the GDP. Trump’s tariff policy is affecting exports.

Inflation has halted government spending (20% of GDP).

~50% is consumer spending, which is at its lowest due to a 41-year high inflation rate.

The situation is looking grim for all sectors. Very grim.

Only two signs of hope:

Japan strikes a trade pact with the US. Somehow trade improves. Production ramps up. Inflation slows down.

If Japan fails to strike a pact with the US, then goods stay in Japan, and domestic inflation eases, which in turn gives room to the BoJ to play around with rate hikes.

4. The US connection

Investors are expecting higher inflation in the US due to Trump’s tariff policies and the “Big Beautiful Bill,” which cuts taxes and promotes more spending. This has already been priced to some extent in the 10-year US yield, which is at 4.3% as you read.

Rising US yields mean three things:

It will increase the rate difference between US and Japan. A good thing for CCT traders who were previously hit by a rise in Japanese rates. To what extent this plays out remains a developing story. But remember, uncertainty is baked at a higher price than other headwinds.

Higher unrealized losses for banks in the US. News reports say US banks are already sitting on $500 billion of unrealized losses - a one-third jump from the last quarter. To put this 500B in perspective, the Silicon Valley Bank run happened when unrealized losses were at $514B. Just saying.

A higher yield means a higher cost of borrowing, which is not good for the “Big Beautiful Bill.” So, in such a scenario, Japan selling its UST holdings would be the last thing Trump wants. And trust me, Japan has quite a few incentives to sell.

To cut losses on its UST holdings.

To pump up the yen, which in turn will make their imports cheaper, which solves for imported inflation.

That’s why the US is urging Japan to use rate hikes to control the entire inflation problem and not resort to selling UST holdings. From US perspective, raising rates will appreciate the yen, which in turn reduces the export competitiveness of Japanese exports, which in turn reduces the trade deficit the US has with Japan.

Conclusion. Why I believe the Bank of Japan is boxed in.

There's only a little for BoJ to play around with. Hiking rates won’t be feasible beyond a point unless the growth completely stalls and Japan goes back to square one with deflation and negative GDP growth. Especially now with such demographics.

For now, the commentary and the sentiment are that the Bank of Japan can continue to hike rates and not be affected by paper losses on its balance sheet. Yes, there will be negative capital and some political backlash for a brief time. But that doesn’t actually break anything, right?

True, but only for the central bank. Too-big-to-fail private insurers and financial institutions are sitting on massive losses. They are not immune to bank runs. There are actual human beings on the ground who have put money in these institutions. They will panic if they see their money vanish in thin air.

Secondly, the rate hikes spike bond yields. This puts fiscal pressure on the government, especially when the borrowing is dominated by short-term notes. They have to be rolled over, right? Financing those interest payments will be costly.

This is still a developing story with new information coming every day. Let’s see how it goes.

That’s it for today. All that has been happening in Japan’s monetary policy. This piece was an attempt to connect the dots and clear my own head.

Next up: Should state development loans be rated just like corporate bonds? (putting it here for accountability)